BioStock’s article series on Drug Development: The Process

The drug development process is a long, painstaking journey that typically takes at least a decade. It involves several steps, and with each step, new and more pressing challenges arise with the potential to jeopardise the approval of a new drug. Due to the complexity and vastness of the issue, BioStock has decided to dedicate an article series to the topic in order to take a deep dive into the intricacies of drug development process and what it takes to get a drug to market.

When we get sick, we pay a visit to the doctor in hopes of getting medicine prescribed that will make all the suffering disappear. Then, we head over to the pharmacy to pick up that “magic potion.”

All of us have, or will, experience this scenario at some point in our lives, but more often than not we take for granted the process that goes on “behind the scenes” to develop such medicines. In this BioStock article series, we will try to elucidate the efforts made by the research and biotech communities that go into making pharmaceutical drugs.

Drug development takes years, sometimes decades

Compared to other products we consume, developing new, innovative medicines can take what feels like ages. More precisely, discovering a promising new compound and taking it all the way to market usually takes at least 12 years on average – even up to 30 years for new areas of medicine.

Many players in the drug development space would find the 12 year mark an optimistic one, especially considering the daunting statistic that only 1 in 5000 new compounds are approved as pharmaceutical drugs by regulatory agencies like the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the US or the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in the EU.

Four stages of drug development

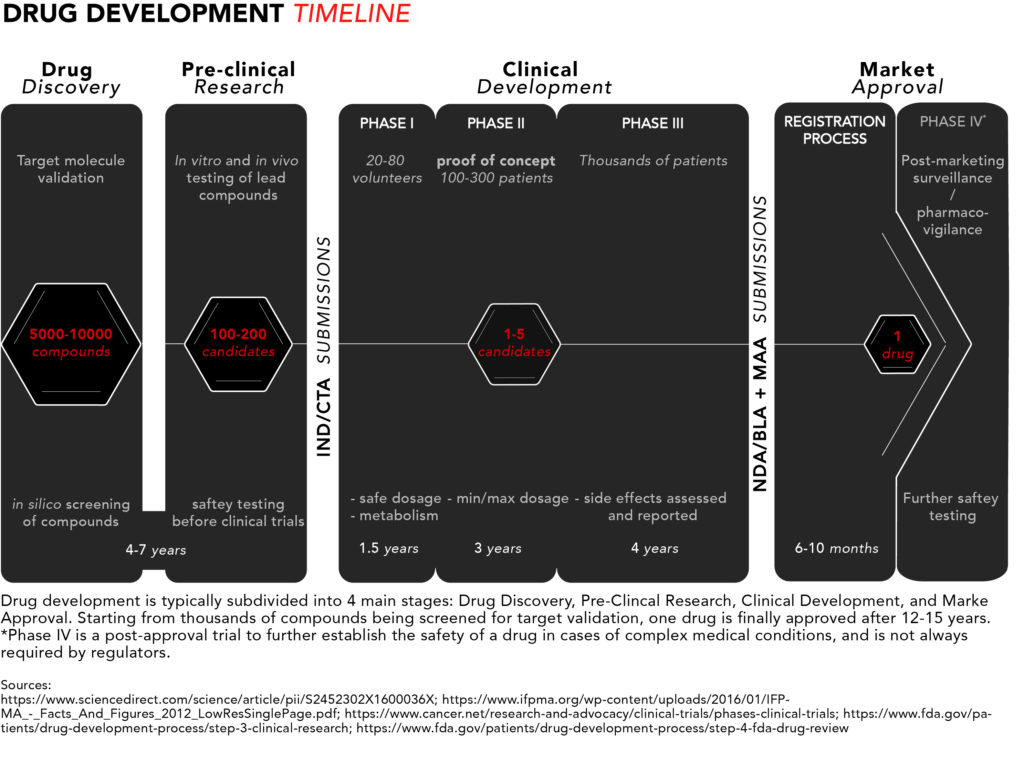

The long journey for pharmaceutical drugs before reaching the market is usually split into four stages: discovery, pre-clinical testing and development, clinical development, and, lastly, market approval.

For a quick snapshot of the process, we have generated diagram summarising the typical drug development timeline presented below.

Now let’s take a closer look from start to finish.

1. Drug discovery

The discovery stage begins with pre-clinical R&D activities carried out in a laboratory setting. Potential target molecules like genes or proteins are identified as new pharmaceuticals. These are molecules that scientists believe could contribute to the development or progression of a disease.

Once a target is found, researchers can perform so-called in silico testing of hundreds or even thousands of potential chemical or biological compounds with the ability to specifically interact with the target molecule(s) to see which ones would influence the target – and hence the disease – the most. In silico refers to the use of computer-generated data to screen, predict, and select which compounds will become lead compounds to be tested further.

2. Pre-clinical research

The discovery phase is followed by a pre-clinical research phase, where the lead compounds are tested in two experimental models: in vitro and in vivo. In vitro, literally translated form the Latin, means in glass and refers to compounds being tested on cells in glassware (nowadays cells are best studied in polystyrene containers). In vivo means in life, and that’s when those compounds go from being tested in cell culture to being tested in live, non-human, animal models.

These settings give researchers an initial idea of how the compounds might interact in humans if they were to be commercialized as pharmaceutical drugs. Once fully characterised, one or more of these molecules are designated as candidate drugs with the desired properties for further development.

The chosen candidates go through rigorous safety testing to make sure they are not toxic for humans before they can begin clinical trials. Overall, the discovery and pre-clinical stages of development can take four to seven years.

At this point, drug companies apply for either an Investigational New Drug (IND) program in the US or a Clinical Trial Application (CTA) in the EU. The respective regulatory bodies will inspect the pre-clinical data and decide whether to approve the continuation of a candidate’s development into clinical trials. The approval typically coincides with the beginning of a drug’s 20-year exclusivity period under a patent.

3. Clinical development

Phase I studies – safety

The few lucky candidates that get through the pre-clinical development stage can enter phase I of clinical trials where they are generally tested on 20 to 100 healthy volunteers to determine whether the candidate drug behaves in the same way in the body as that indicated in pre-clinical trials. The safety profile – or toxicity – of the compound is, once again, the main concern, but this time in humans. This includes testing a safe dosage, how the drug is metabolized, and how long it remains active inside the body.

Of note is the fact that phase I clinical trials tend to exclude women. For safety reasons, regulatory authorities recommend excluding women of childbearing age in early clinical testing until drug candidates pass all toxicity screenings. According to the FDA, a phase I trial can take several months.

Phase II studies – proof of concept

In phase II, the candidate drugs are tested on 100 to 300 patients with the disease that the candidate is intended to treat or cure. Efficacy joins safety as minimum and maximum dosages are determined – focus is placed on establishing data for determining the doses to be used in the next phase of studies. Phase II typically takes up to two years.

Phase III studies – regulatory proof

Phase III is the last step in the studies before requesting approval from pharmaceutical regulators. The number of patients included in a phase III study typically ranges in the thousands to make certain enough data is collected in order to convince regulators that the drug works as intended. At this stage it should be made obvious that the drug is safe for humans and has the intended clinical efficacy.

This is also where the researchers document and report any side effects experienced by patients, thus patients need to be exposed to the drug for long periods of time in order to make sure those side effects are properly assessed. Phase III takes one to four years on average.

4. Market approval

Registration process

Once the clinical trials are complete, applications for market approval called New Drug Application (NDA)*/Biologics License Application (BLA) in the US and the Marketing Authorisation Application (MAA) in the EU, which can comprise 100,000s of pages of documentation summarizing all the data collected and making the case for approval, are submitted to the FDA and/or the EMA, respectively.

*Note: some new drugs are categorised as New Molecular Entities (NMEs), drugs with active ingredients yet to be approved by the FDA or other regulatory authorities, and those require an NME NDA application.

Preparing these documents for submission can take several months, and for the authorities to process the applications normally takes around 6-10 months.

Market launch

If the pharmaceutical regulatory authorities decide to approve the application, the product can be launched on the market.

At this point, price negotiations begin between the producers of the drug and the potential buyers (governments or insurance companies). The price negotiating process can differ from country to country. In the Europe, EU member states follow specific EU guidelines, but some guidelines vary. Take Sweden, for example, where pricing regulations follow EU rules, while reimbursement regulations are set at the national level. For a more detailed look, read here.

Meanwhile, in the US, price negotiations take place between the pharma companies and private insurers, leaving the national government out of such negotiations. This leads to higher prices for such drugs in the US compared to Europe and other developed countries.

Phase IV studies – marketing and safety monitoring

In some cases, after market approval, regulators will require phase IV trials for post-marketing safety surveillance (pharmacovigilance). This course of action usually takes place to ensure that newly approved drugs do not interact with other forms of medication. They are also necessary for further safety testing, especially in cases of drugs used to treat complex medical conditions or pregnant women who are unlikely to have been involved in earlier trials. It can also be relevant when the drug targets a rare conditions and clinical trials therefore have been limited in terms of the number of included patients.

Summing up, 12-15 years later is when the long journey of drug development ends. However, we have barely touched upon the challenges associated with the development and approval process. Stay tuned for the second part of this series where we will take a look at some of the major hurdles companies face when taking one of their products to market, including the high costs related to drug development.

Part II: Challenges Associated with Drug Development

Part III: A Brief History of Regulatory Affairs

Part IV: Making Treatments More Accessible

Part V: The Success of Orphan Drug Designation