BioStock’s article series on drug development: Making Treatments More Accessible

Regulations put in place for ethical, safe and effective drug development gives are important. However, they represent a significant burden on drug companies adding longer development times and heavy costs. Those burdens translate to a longer journey to market approval for new therapies, and thus more stress on patients in urgent need of such medicines. With this fourth article in BioStock’s series on drug development, we take a look at some of the more recent rules put in place by regulatory agencies in an attempt to speed up the drug development process and giving patients quicker access to new drugs.

With the rise of new and essential drug development regulations over the last century, the time it takes to put a new medicine on the market has increased significantly and the costs have followed suit.

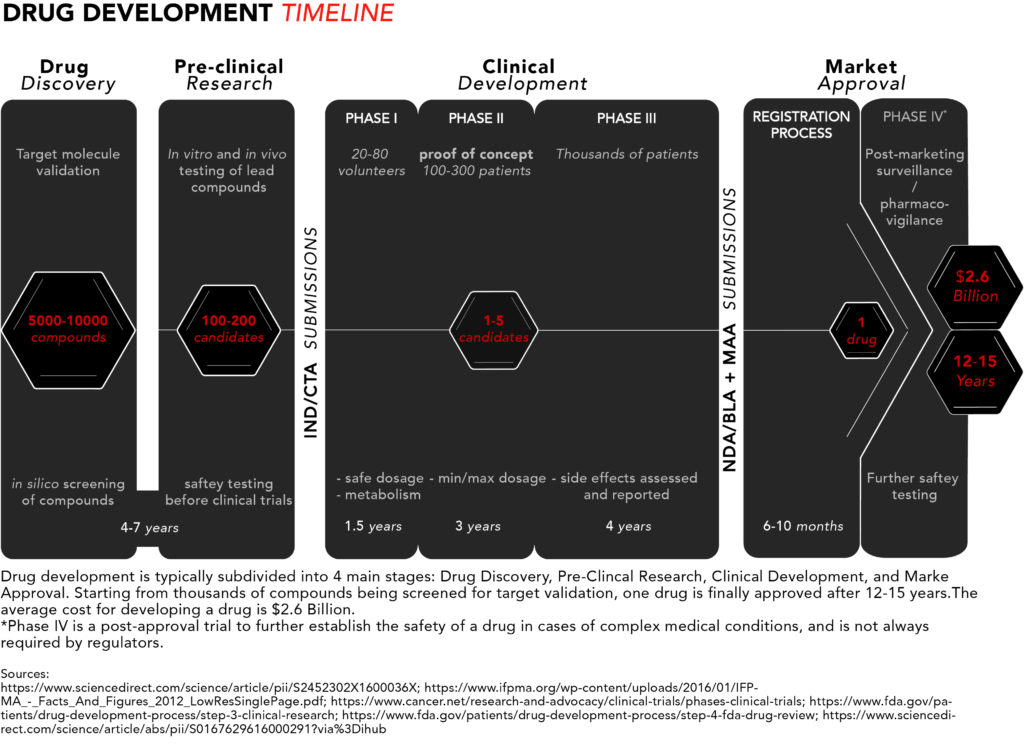

Here’s a schematic summarising the drug development process. For more details refer to Parts I, II, and III of this article series.

Patients with rare and incurable diseases who have an urgent need for new and effective drugs may find themselves hearing about potential blockbuster therapies in the early stages of drug development but having to wait several years – that their disease might not let them have – to get access to such medicines.

Patients with rare and incurable diseases who have an urgent need for new and effective drugs may find themselves hearing about potential blockbuster therapies in the early stages of drug development but having to wait several years – that their disease might not let them have – to get access to such medicines.

Recently, there has been a strong push to reduce the time it takes for some medicines to get past clinical trials and past regulators onto the market, where they become accessible to prescribing physicians and, as is the final goal, to patients. The pressure has led to initiatives by both the FDA and EMA to create new rules aimed at improving drug development timelines.

FDA directives

The FDA has four directives aimed at speeding the availability of drugs necessary for treating serious diseases: Fast Track, Breakthrough Therapy, Accelerated Approval, and Priority Review.

Fast Track is designed to get new drugs to patients with serious medical conditions much earlier than when following the traditional regulatory process. In order to meet the Fast Track requirements, the drugs should fill an unmet medical need, meaning that no other therapy is currently available.

Fast Track designation gives companies access to more frequent communication with the FDA, which, among other things, includes discussion about the design of proposed clinical trials. This designation also gives eligibility for Accelerated Approval and Priority Review if candidates meet specific requirements (see below).

A Breakthrough Therapy designation is similar to Fast Track and involves the same requirements. In addition, however, it requires positive preliminary clinical data as evidence that a candidate is a substantial improvement over existing medicines at the level of irreversible morbidity or mortality (IMM) or on symptoms that represent serious consequences for a disease.

If received, this designation gives a candidate access to high-level clinical drug development guidance, as well as organizational support from senior managers at the FDA – something that Fast Track does not provide.

Most drugs in development are approved for market launch if they meet “clinically significant” endpoints or that have a “clinical benefit,” i.e., statistically significant clinical data indicating that the experimental treatment in question is able to improve survival times. Accelerated Approval designation is given to candidates intended for serious conditions and that meet “surrogate” endpoints, meaning a clinical data point(s) that is thought to predict a clinical benefit of a drug, but which requires less time to reach in testing.

A good example of a surrogate endpoint is progression-free survival (PFS) in the case of cancer, i.e., how long the patient with cancer survives without evidence that the tumor has measurably grown or metastasized. This kind of measurement takes considerably less time to evaluate compared to overall cancer survival. The FDA does require clinical trials to be conducted post-approval to confirm clinical endpoints, and one study in particular has shown that 20 per cent of oncology that received accelerated approval were ultimately validated in confirmatory trials to have an effect on overall survival.

Priority Review designation is meant to shorten the standard regulatory review process from an average of 10 months down to 6 months or less when a New Drug Application (NDA) or a Biologics License application (BLA) is submitted by the drug company. This designation is given to pharmaceutical candidates that would constitute significant improvements in the safety or effectiveness of the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of serious conditions.

If granted, a drug with priority review designation is given, as the designation suggests, priority over drugs submitted for standard review, thus getting the attention of regulators sooner.

European initiatives

The EMA has two initiatives with similar goals as the FDA versions above, PRIority MEdicines (PRIME) and Adaptive Pathways (AP). Both of these initiatives are based on already existing EMA regulations.

Candidate medicines eligible for PRIME receive regulatory support from the clinical trial design stage all the way to market authorization, including accelerated assessment, which is similar to the FDA’s Priority Review, meaning that once a Marketing Authorisation Application (MAA) is submitted to the EMA, regulators will prioritize that application over standard review application. Therefore, that application will be reviewed in 150 days or less, instead of 210 days, which is the average standard review time.

PRIME’s eligibility criteria are based mainly on a candidate’s potential to offer a major therapeutic advantage over existing medicines and be able to benefit patients with unmet medical needs.

AP is an innovative tool in healthcare systems and part of the EMA’s strategy to let patients with serious illnesses early gain access to experimental drugs, and it’s based on regulatory processes already in place, such as scientific advice and compassionate use.

Provided the pharmaceutical candidates are meant for unmet medical needs, AP aims for a step-by-step approval of a drug: a drug is first approved for a small group of patients (when little scientific evidence exists), then for larger groups of patients as more evidence is gathered.

With this approach, talks with regulators to speed up the approval process begin before the initiation of phase II studies. These talks continue rigorously throughout the rest of clinical development and through approval.

Compassionate use and right to try

In some rare cases, the AP initiative unshackles some medicines from the strictest regulations in order to give otherwise terminal patients at least a chance to try an experimental treatment yet to be approved. This can be done under the compassionate use provision set in place by the EMA, which grants patients access to a candidate treatment before market approval, as early as late phase II of clinical trials.

Similar provisions exist in the US. The FDA has three expanded access programs that could grant patients earlier access to some experimental drugs, one for individual patients, one for medium-sized patient populations, and one for widespread use.

Just last year, the US government passed a law allowing patients to gain access to unapproved drugs without having to go through the FDA first. This provision, called Right to Try, gives patients the right to go directly to the company developing a drug and making a request to try it. This puts all responsibility exclusively on the company willing to comply with the wishes of a patient. Although the FDA isn’t directly involved, a drug eligible for Right to Try must have passed the safety thresholds set by a phase I clinical trial and be subject to an investigational new drug (IND) application.

The good and the bad of faster approval

Right to Try has received praise for its commitment to grant terminally ill patients’ quicker access to potential treatments. However, the provision has also come under a lot of scrutiny by experts who are sceptical of experimental drugs bypassing the FDA to reach patients.

Other provisions have received similar pushback by national agencies. For example, there have been reports of Germany’s Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG) worrying that fast track provisions by the EMA will become the new norm, creating loopholes for pharmaceutical companies to take advantage of.

Another initiative meant for speeding up drug development that has received plenty of criticism is the Orphan Drug Act of 1983 (see Part III of this series for a short historical overview of regulatory affairs in drug development). The bill required the FDA to offer incentives to pharma companies wanting to develop drugs for rare diseases, and it’s been successful. The success has led to speculation that companies take advantage of these incentives to maximise profit, thus creating a monopoly in the orphan drug market.

The EU followed in 2000 by creating the Committee for Orphan Medical Products (COMP), which gives drug makers similar incentives to develop orphan drugs but has tougher requirements compared to the FDA.

Note: due to magnitude of the ODA’s impact on drug development, the next and final part of this series will be dedicated exclusively to the Orphan Drug Act and how it has shaped drug development in recent years. So, keep an eye out for this segment next week!

New solutions on the horizon

All said and done, the strict regulations set in place to protect consumers are a necessary aspect of drug development as history tells us. However, several inefficiencies remain, and more can and should be done to reduce the time and costs of drug development in order to get patients quicker access to new, innovative drugs.

Artificial intelligence (AI) may be the answer drug companies and patients are looking for. Several big pharma firms are betting on AI to speed up their R&D and clinical development times. For example, GSK’s 33 MGBP investment in Exscientia’s AI technology platform for small molecules discovery was one of the biggest deals of 2017 between big pharma and AI. More recently, the AI startup Cyclica announced Bayer was using its AI drug discovery platform. Read more about some of the latest deals here.

The potential benefits of AI within life science are enormous, so much so that BioStock will dedicate a full article series to this exciting field later this fall. Stay tuned!

Part I: The Drug Development Process

Part II: Challenges Associated with Drug Development

Part III: A Brief History of Regulatory Affairs

Part V: The Success of Orphan Drug Designation